1.

On the southern edge of Paris, in one of those nowhere zones south of Necker where the fourteenth and fifteenth arrondissements collide just inside the Boulevard Périphérique that chokes the city center in smoke, a five-thousand-square-foot basement houses the Bureau des Objets Trouvés, or the Bureau of Found Objects.

Patrick Cassignol, who has directed the Bureau des Objets Trouvés for over a decade, likes to call the agency’s vast underground storeroom “Ali Baba’s cave.” Inside, six kilometers of identical grey shelves hold carefully labeled key rings, wallets, cell phones, shopping caddies, stuffed animals, prosthetic limbs, and lonely gloves. The agency maintains a surprisingly simple system of valuation to account for the hundreds of thousands of items it receives each year. If an object is valued at less than one hundred euros, it is kept for four months; more valuable items are stored for one year. After the designated period, unclaimed items are either donated to charity or destroyed.

In addition to processing everyday items, the Bureau des Objets Trouvés also maintains a private museum of miscellanea. The musée de l’insolite at the Bureau des Objets Trouvés houses a whimsical collection of oddities: an unclaimed funeral urn, a taxidermied lobster found at the Orly airport, a nineteenth-century sword, a human skull retrieved from a train station near the Catacombs, two-hundred-twenty-two pounds of copper wire, a collection of forsaken wedding dresses, and even a few shards of concrete from the World Trade Center—the Berlin Wall of my generation—recovered from an abandoned suitcase along with the bright orange vest of a New York City transit employee.

When asked in a recent interview for The New Yorker why the agency is called the Bureau des Objets Trouvés rather than the Bureau des Objects Perdus, Cassignol responded pragmatically: “Because we do not know if they were lost or stolen. We know only that they have been found.”

Lost or stolen, what these items have in common is that someone, somewhere, had the heart to reach down and pick them up, and in a fit of generosity, to deposit them at the police prefecture with the absurd hope that these orphaned objects might one day find their way home. This generous individual, the finder, is referred to as the inventeur, or “inventor,” of the object; the designation suggests that the object’s value and identity derive entirely from the quality of having been found.

2.

I found myself living in the nineteenth arrondissement of Paris, a working-class neighborhood on the Right Bank of the Seine, by sheer force of circumstance. I would say that I am lucky to be living here, but I am distrustful of the idea of luck, which smacks of entitlement and the blind apathy of faith.

I chose to live the nineteenth arrondissement (or rather, the nineteenth arrondissement chose me, as my mother used to say of the stray cats that my parents would occasionally agree to take in when they wandered, purring, out of the neighboring fields), because with the exception of some of the dark corners on the northeastern slope of Montmartre, the nineteenth arrondissement was the only neighborhood on the Right Bank that I could afford.

There are two types of people in Paris: Left Bank loyalists, and those who swear by the Right Bank; a river runs between them.

The Left Bank is a picture of Paris as it exists in every foreigner’s imagination, with warmly lit cafés on winding cobblestoned streets and hidden courtyards where ancient fountains babble for no one’s ears in particular. The place just aches with romanticism. The Left Bank is home to the Latin Quarter, Saint-Germain-des-Près, and Montparnasse, those illustrious enclaves of French intellectualism where everyone from Charles Baudelaire to Jean-Paul Sartre and Marguerite Duras had their humble beginnings.

I once went wandering there with a French banker that I met while returning my Vélib to a bike share stand. We were both on our way to a convenience store that stays open until two in the morning on the Place Saint-Michel, across the Seine from Notre Dame. He led me through the empty streets to the former home of the beloved French singer Serge Gainsbourg, hidden behind a densely graffitied wall on the Rue de Verneuil. He offered to buy me a drink, but it was already after midnight, so I took him to a cavernous speakeasy called Le Bar on a side street between Odéon and the Jardin du Luxembourg. Le Bar looks a bit like the Korova Milk Bar in the opening scene of Stanley Kubrick’s filmic adaptation of “A Clockwork Orange,” but without the glossy statues of naked women clad in nothing but in curly white wigs. We were drinking whiskey at a low table in the back when a drunk but pleasant enough poet approached us and asked if he could recite us a few lines of poetry. The three of us ended up wandering around the Hôtel des Invalides, where Napoleon is buried, to watch the sunrise over the Seine from the Pont Alexandre III. This is the Left Bank. It is a place of dreams and delusion.

The Right Bank, across the Seine, is home to most of the major tourist attractions in Paris. I still marvel at the arrow-straight path that runs from the Louvre through the Jardin des Tuileries and the Place de la Concorde all the way to the Arc de Triomphe at the far end of the Champs Elysées. Most foreigners stick close to the Seine and only stray north to visit the Centre Georges Pompidou, the largest museum of modern art in Europe, or to follow the footsteps of Amélie Poulain in Montmartre. But if you are priced out by the fashionable boutiques in the Marais and wander far enough north on the Boulevard de Strausbourg to the Gare de l’Est, you will cross an invisible frontier around the Boulevard Saint-Martin and enter the Paris beloved by progressive Parisians.

Don’t even bother with the lines at L’As du Falafel on the Rue des Rosiers in the Jewish quarter; go to the Daily Syrien, a newspaper stand qua food counter on the bustling Rue du Faubourg Saint-Denis for the best falafel in Paris. The neighboring Canal Saint-Martin is like the New Brooklyn of Paris, if Greenpoint spoke a dozen African languages instead of Polish and the culinary scene and nightlife in Williamsburg were somehow less pretentious. Further north along the canal, up the hill from the micro-Chinatown on the corner of the Boulevard de la Villette and the Rue de Belleville, the underappreciated Parc de Belleville boasts some of the best views of Paris at sunset.

This is the Paris I call home.

3.

I was perusing the permanent collection at the Musée de l’Orangerie in the Jardin des Tuileries when I came across a newly opened exhibition on the “sources et influences extra-occidentales” of Dadaism, which explores the impact of indigenous African, American, and Oceanic art on European avant-garde movements in the early twentieth century. My friend Vincent, the most dedicated museum-goer I know, had convinced me over drinks to buy an annual pass to the Musée de l’Orangerie, which includes unlimited access to the Impressionist galleries at the nearby Musée d’Orsay. I like to go to the Musée de l’Orangerie when I am feeling overwhelmed by the frantic pace of the city; eight of Claude Monet’s iconic water lily murals are on permanent display there, and those swirling pastels never fail to calm my nerves.

The new exposition at the Musée de l’Orangerie attempts to destabilize the dominant narrative that Dadaism was an inherently European movement. In the wake of colonial conquest and exploratory expeditions in Africa, the Americas, and Oceania, thousands of indigenous artifacts began appearing on auction blocks and in flea markets in Europe around the turn of the twentieth century. Despite knowing knew very little about the original meaning and function of these objects, which were treated as indigenous artifacts rather than works of art in their own right, European artists, critics, and dealers soon began collecting them for their unique aesthetic value and exotic allure. The highly stylized treatment of the human figure, pictorial flatness, vivid color palette, and fragmented shapes that have come to define the aesthetic of the European avant-garde can be attributed in large part to the colonial encounter between Western artists and the non-Western cultures they colonized.

Contemplating a glass display case of wooden Makonde masks, I am reminded of Cassignol’s comment on the value of the found object. These indigenous artifacts were not lost; they were stolen. This is the story of colonialism. To Marcel Duchamp and the Dadaists, it didn’t matter that these indigenous artifacts had a history, a function, and a symbolic significance of their own; they saw them primarily as found objects, whose value and identity were gleaned from their quality of having been found, much like the endless rows of everyday items collected at the Bureau des Objets Trouvés.

Inspired by Pablo Picasso’s incorporation of everyday materials such as newspapers, matchboxes, or rope into his Cubist collages, the Dadaists wanted to demonstrate the social construction of artistic value by transforming found objects into works of art (I am tempted to place “art” in quotation marks, but I will leave that debate for another day). Duchamp called these pieces “ready-mades”: manufactured objects whose artistic value and identity derived entirely from the artist’s intent, along with the context into which the found object was placed by the artist (a porcelain urinal poised on a pedestal in an art gallery, for example, to cite one of Duchamp’s most controversial pieces).

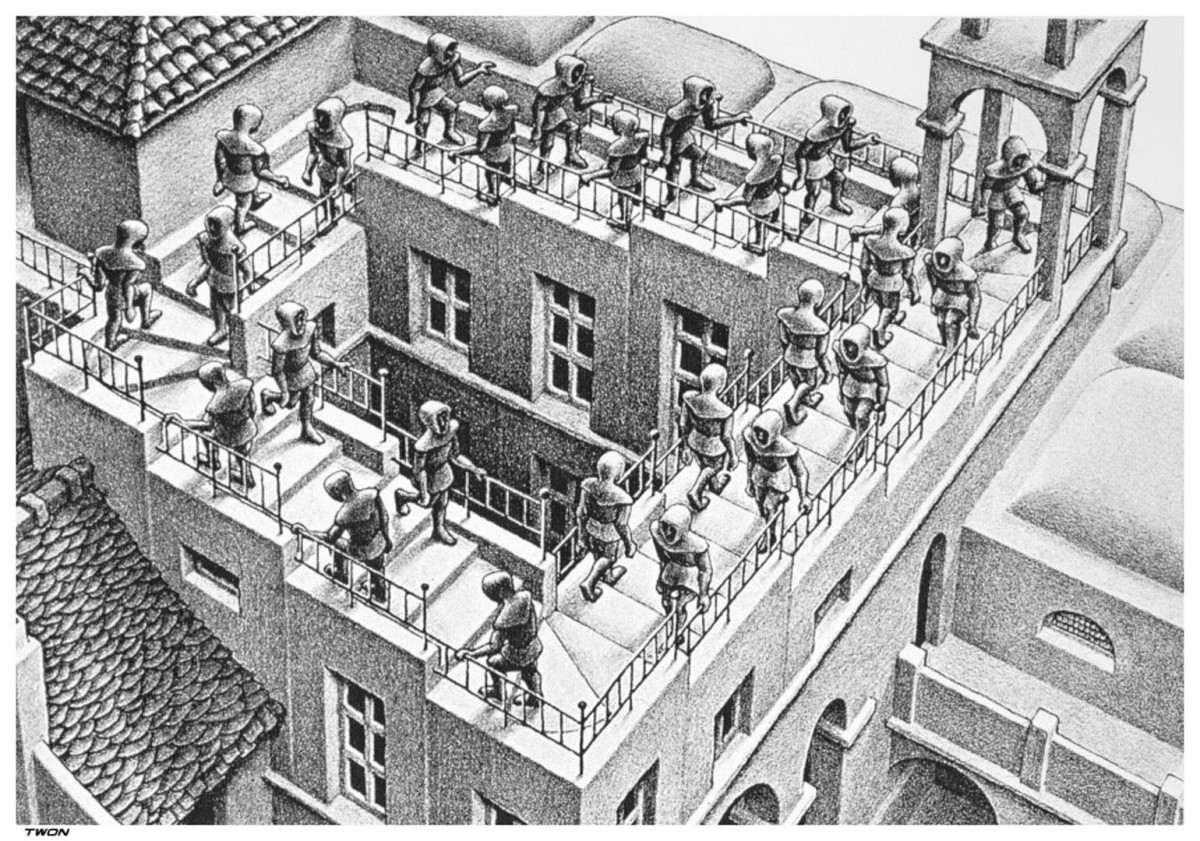

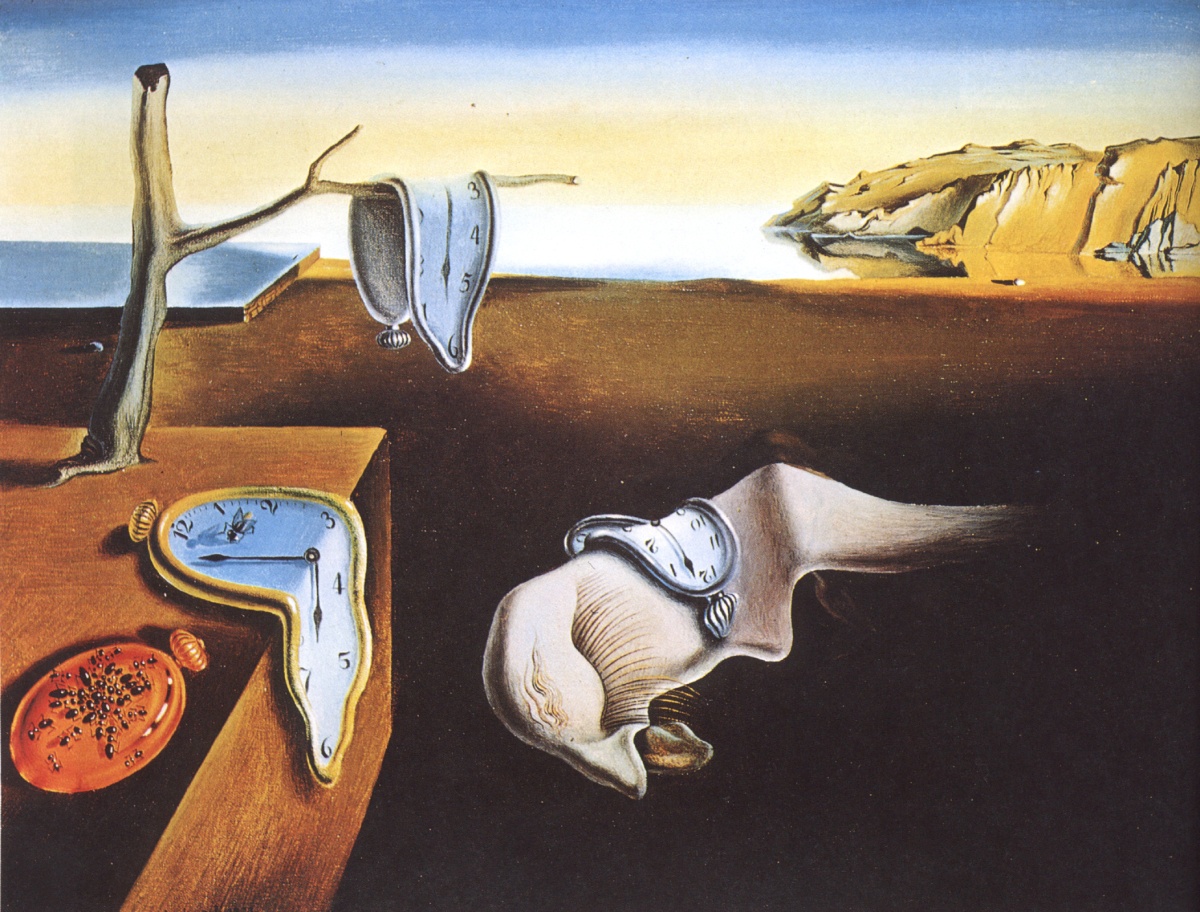

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Justifying the artistic value of his famous “Fountain” piece in an editorial published anonymously in the May 1917 edition of the avant-garde magazine The Blind Man, Duchamp writes: “whether [the artist] with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view—created a new thought for that object.”

Duchamp’s idea was that by abstracting or isolating existing man-made objects from their intended environments, he could disrupt the symbolic systems of value—including artistic value—according to which all economic relations are expressed. The transgressive potential of the found object is perhaps best exemplified by the American avant-garde artist Man Ray’s 1921 sculpture “The Gift,” in which a common flatiron has been rendered useless by a vertical column of brass tacks glued down the appliance’s smoothing center. The domestic familiarity of the found object was intended to reinforce the abstraction of its artistic appropriation, producing what Sigmund Freud first described in 1919 as the unheimlich, or the uncanny, a feeling of foreign familiarity.

The avant-garde artists of the early twentieth century had an undeniable knack for sowing scandal in elite intellectual circles. Assuming Duchamp’s work can be said to have any artistic value in the first place (a debate that persists primarily amongst academics and art critics, whereas the general population seems to have largely discredited or simply forgotten about his work), one of the most fascinating discussions surrounding Duchamp’s “Fountain” piece concerns the status and authenticity of the porcelain urinal featured in his work.

Duchamp’s original “Fountain” was never exhibited publicly. After the piece was initially rejected for the first annual exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York, the American art collector Alfred Stieglitz agreed to display and photograph the porcelain urinal in his private studio. A staged photograph of Duchamp’s piece was then published in The Blind Man, cited above, and the original porcelain urinal was subsequently destroyed.

But despite his stated intention to disrupt systems of artistic and economic value, increased interest in Duchamp’s famous “Fountain” piece in the 1950s and 60s encouraged the artist to authorize an estimated sixteen reproductions. Of these “authentic” reproductions, eleven have been included in museum collections around the world, and four are owned privately; one has been indefinitely lost.

Ironically, however, the facile reproducibility of Duchamp’s iconic piece has finally succeeded in confounding the systems of value that the artist initially sought to disrupt. Reproductions of Duchamp’s “Fountain” are notoriously difficult to authenticate. Allegedly unauthorized reproductions of the piece have infuriated connoisseurs and befuddled potential collectors willing to pay millions for the privilege of owning a piece of Duchamp’s controversial legacy: a pseudonymous signature scrawled hastily on a porcelain urinal.

The exhaustive debate surrounding the relative artistic and economic value of Duchamp’s “ready-mades” often obscures the simple fact that “Fountain,” like much of the work of early Dadaists, originally consisted in a found object: prosaic, rudimentary, vulgar. Perhaps the only museum in which Duchamp’s work unquestionably merits inclusion is the musée de l’insolite at the Bureau des Objets Trouvés.

4.

Paris has a problem that is common to many of the iconic capitals of the world; the city has been so colonized by the international imagination that to the untrained eye it looks like there is nothing left to find. Paris has so many major monuments and historical landmarks that any sane itinerary to visit them all would take weeks to complete. After nearly a decade of passing through Paris, I still haven’t toured the Catacombs, a two hundred mile network of underground ossuaries where some six million bodies are buried, and I only recently took my first trip to the Château de Versailles when my American partner visited me in Paris a few weeks ago.

When I first visited Paris in March 2009 on my way south to a study-abroad program in Avignon, I remember feeling overwhelmingly disappointed in the city, and then even more disappointed in myself for having failed to grasp the essence of a place that had existed so vividly and for so many years in my imagination. Had I missed something essential? Had I done something wrong?

They say there is a mental ward in the Hôpital Sainte-Anne in Paris for Japanese tourists who are traumatized upon discovering that Paris isn’t what they thought it would be, all buttery croissants and effortlessly chic women wearing stripes and smelling of Chanel No 5. Mental health professionals call it the “Paris Syndrome,” a psychosomatic tailspin triggered by “the shock of coming to grips with a city that is indifferent to their presence and looks nothing like their imagination,” as Chelsea Fagan describes it an article for The Atlantic. The Japanese Embassy in Paris even has a 24-hour emergency hotline for tourists suffering from the condition and seeking medical help.

It is easy to dismiss the “Paris Syndrome” as an indelibly first-world disorder, or the result of an unforgivably naïve worldview. But there is something profoundly alienating about the disjuncture between the “City of Lights” as it exists in the international imagination and Paris as a living, breathing city: an unfriendly place, filthy in parts, where inequality and crime flourish as they do in any urban center. That cognitive disconnect can be disorientating.

But at the same time, Paris still plays something of a caricature of itself, especially in the central arrondissements that border the Seine, and it can be surprisingly difficult to break through the city’s glossy veneer. Writing in the journal that I kept the summer I lived in Nice, that ochre jewel of a city on the French Riviera, I described Paris as a place “where people fuck and drive and drink and smoke and shop and flirt and maybe even fall in love, but where no one actually seems to live.” In Paris, the café terraces are bursting at all hours with fashionable men and women whiling away hours over espressos and chain-smoking cigarettes. With the exception of the service industry, I had never actually seen anyone going to work. Where were the lawyers, the physical therapists, and the bankers, and where and when did they find the time to work between boozy two-hour lunches and the late afternoon apéritif, or cocktail hour?

Even after passing through Paris a half-dozen times, always on my way someplace else, the city still felt unreal. I could stock up on any number of high-end skin care products at the pharmacy, but where did Parisians go when they got sick? I knew where to find wicker baskets and vintage mirrors and decorative lamps, but where could I buy a replacement light bulb? How could people afford to get dressed in a city known for its high fashion and luxury accessories, and can anyone really tell the difference between drugstore brand makeup and the gold tube of Yves Saint Laurent mascara that a saleswoman once tried to sell me for 36€ at Sephora?

And where was the gritty underbelly of the gilded city? I was sure it existed somewhere, but I didn’t know where or how to find it. I had encountered the roaming Eastern European roumis that beg in front of Notre Dame and the predatory groups of Senegalese men that sell key chains and trinkets at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, but I had never come across the kind of poverty of which one finds traces on every street corner in American cities.

And then one day I took a wrong turn coming down the hill from Sacre Coeur, and suddenly I found myself in the midst of a bustling sidewalk bazaar near La Chapelle, where improbable crowds of African and Middle Eastern men loiter in groups devoid of women and traveling merchants sell an off-brand version of everything imaginable, their sundry wares unfurled on blankets on the sidewalk. Here, I remember thinking, is the Paris I have been looking for. It had been there all along; I just hadn’t found it yet.

5.

Nearly a center after Duchamp’s porcelain urinal scandalized the art world, the French filmmaker Agnès Varda returned to the subject of the found object in her 2000 documentary, Les glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I), an idiosyncratic film about finding value in the everyday. The documentary opens with an extended sequence of a single repeated motif: the rounded back of an agricultural worker as she crouches over a modest crop, following in the tracks of modern farming equipment to collect what the machines have left behind. In the opening scene of Varda’s film, shots of contemporary potato gleaners in rural Beauce are intercut with the image that accompanies the definition of glanage, or “gleaning,” in the Dictionnaire Larousse, a black-and-white reproduction of Jean-François Millet’s 1857 painting Les glaneuses. In each of these images, the gesture of the gleaner remains unchanged: her head is down, her arm extended, her back hunched in a humble posture of industry and bleak necessity.

The film then cuts abruptly to the streets of a gloomy Paris, under the elevated tracks of the metro as it runs away from the city center towards the banlieus, where urban gleaners pick through the leftovers of an open-air market: bunches of wilted parsley, small apples, blemished tomatoes. After another abrupt cut, Varda’s camera pauses in patient admiration before the imposing canvas of Jules Breton’s 1877 painting La glaneuse. The low perspective of Breton’s naturalist tableau magnifies the female gatherer in the foreground, who stands dignified with a healthy harvest of wheat slung over her broad shoulder. On the horizon, the red orb of the sinking sun is half visible, casting a warm glow on the gleaner’s tanned skin. The commanding figure of Breton’s glaneuse then fades into a shot of the filmmaker herself, positioned in a tall mirror before her own camera with a bundle of freshly picked wheat proudly balanced on her shoulder. “Parce que moi aussi . . . je suis une glaneuse” (“Because I myself am a gleaner”), Varda declares.

Les glaneurs et la glaneuse is a film about the time-honored tradition of artistic appropriation, but it is also, and perhaps more poignantly, an exploration of the economic, social, and racial margins of French society at the turn of the twenty-first century. In Les glaneurs et la glaneuse, Varda reflects on the social alterity of the gleaner at a historical moment when globalization, hybridization, and mass migration were increasingly perceived as an existential threat to the integrity of the French nation, its language, and its culture. Varda trains her patient camera on those organic entities living beyond the invisible frontiers of mainstream society, at the edge of financial security, in the margins of the law, and on the outskirts of urban centers: the itinerant laborers, the caravan dwellers, the illiterate immigrants, the misshapen potatoes, and the grapes left to rot.

The gleaners of Les glaneurs et la glaneuse are a delightful, eclectic bunch. Some of them rely on gleaning for basic sustenance and survival, picking through the dirt to collect produce that has left behind, scouring the beach for oysters washed up after a storm, gathering fallen fruit off of orchards grounds, or dumpster diving in back alleys to recover discarded scraps, stale bread, or packaged food that has passed its expiration date. We meet a man who claims to have eaten nothing but salvaged food for over a decade without once getting sick, and a young chef in a two-star restaurant who gathers his own herbs out of frugality, a commitment to environmental sustainability, and an aversion to conventional agricultural practices. Both men share a preference for food found first-hand, rather than purchased through a third party.

The gleaners in Varda’s documentary don’t just gather out of necessity; like Varda herself, they are artists, too. Varda interviews a brick mason who in his spare time constructs disturbing sculptures out of discarded dolls and an artist who incorporates wooden whirligigs, broken utensils, and scraps of leather into richly textured assemblages that are reminiscent of Picasso’s cubist collages. Louis Pons, the collage artist in Varda’s documentary, describes his peculiar collection of found objects as a “dictionary [of] useless things”; “People think it’s a cluster of junk,” Pons says, “but I see it as a cluster of possibilities.”

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

6.

A cluster of possibilities: that is what I sought in Paris when I moved here last January. Like any good explorer, I was fleeing something back home; on this most recent flight to France, I was fleeing the notoriously harsh Chicago winter and the lingering trauma of a painful breakup.

My first apartment in Paris was under the eaves of a Haussmanian residency above the noisy tracks of the Gare de l’Est on the Rue de Lafayette. My fifth-floor apartment had a stunning view of Sacre Coeur to the west, but for some reason, there was something about the psychic energy of the place that aggravated my insomnia. I would stay up until the wee hours binging on Bojack Horseman on Netflix or sitting on my windowsill watching the seamstress that lived across the courtyard work throughout the night.

After a month, I lugged my suitcases from the tenth arrondissement to a dingy apartment near the Porte de Clignancourt north of Montmartre. My decision to live there was based almost entirely on the fact that the apartment had a piano and a washing machine. My friend Simon had driven into town from Compiègne to help me move, and he immediately sensed my distress upon finding the apartment in a state of moldy disarray. He played darts while I immediately went to work scrubbing what appeared to be decades of grime and grease off of every surface accessible to a sponge. When I fell miserably ill a few days after my move, I informed my landlord that I would be cutting my contract short. To this day, I am not sure if it was the black mold infestation in the apartment or the frigid march I attended in protest of the newly inaugurated President Trump’s immigration policy that caused my malady; in any case, I was unhappy, and I needed to move.

Out of desperation, I impulsively rented an apartment beyond my financial means in the twentieth arrondissement, just up the street from the Buttes Chaumont, my favorite park in Paris. The penthouse of a six-floor walkup, the apartment was sprawling by Parisian standards; it had a bedroom with a real double bed and a desk where I could work, a kitchen, a living room, an alcove that served as a dining room, and a bathroom with a shower that didn’t make me feel claustrophobic—a rare luxury. I moved to the twentieth arrondissement shortly before the French presidential election, and when the French politician I was casually dating at the time won a pretend election among friends on social media, he recorded his acceptance speech in front of the giant map of the world that hung above the couch in my living room. It was there, perched above the tiled rooftops of Belleville, that I fell in love with this bohemian oasis in northeastern Paris.

7.

One of my favorite characters in Varda’s Les glaneurs et la glaneuse is a bespectacled man named Alain, an urban gleaner in his late thirties or early forties with a Master’s degree in Biology. We first meet Alain nibbling on a wilted bunch of parsley at an open-air market outside of the Gare de Montparnasse in the fifteenth arrondissement. When Varda approaches him to ask if he often snacks on fresh herbs, he surprises her by rattling off a list of vital nutrients found in parsley: beta carotene, magnesium, vitamins C & E, and zinc. Varda then follows Alain to the basement of a cultural center on the outskirts of Paris, where he volunteers every evening teaching French to a group of African immigrants. He is patient and full of encouragement. He asks one of his students to define “success.”

Alain is the final figure we meet in Les glaneurs et la glaneuse, and his character encapsulates the core of the story that Varda has been telling all along. For Varda, gleaning is not just about sustenance and survival; it is also an inherently political act. On the socioeconomic margins of French society, the gleaner represents a figure of resilience and resistance against the hegemonic forces of global capitalism, political conservatism, and cultural or linguistic purism.

Alain’s students, mostly immigrants from former French colonies in West and Central Africa, are gleaners, too. The French empire has fallen, and here to glean its abandoned crop are its former colonial subjects, the future native speakers of a new French vernacular. Or, to quote the sixteenth-century poet Joachim du Bellay, who defended linguistic appropriation as a form of creative colonization, “So the Roman Empire grew by degrees, / Till barbarous power brought it to its knees, / Leaving only these ancient ruins behind, / That all and sundry pillage, as those who glean, / Following step by step, the leavings find, / That after the farmer’s passage may be seen.”

By the mid-sixteenth century, when Du Bellay was writing, France had finally begun to resemble a modern nation-state. In 1539, the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts declared French the sole administrative language of France, replacing Latin, and in the same year, the first official French grammars were published. And by the time Du Bellay’s Défense et illustration de la langue française (Defense and Illustration of the French Language) was published in 1549, the contiguous territory of France had been incorporated under a centralized (albeit irregularly executed) set of administrative laws.

At a time when regional dialects continued to undermine the dominance of the administrative language and national borders remained subject to continuous contestation, Du Bellay defended the French vernacular as the burgeoning seed of France’s nascent national consciousness. Du Bellay explicitly links poetry to proto-national politics in the opening sonnet of Les antiquitez de Rome (The Antiquities of Rome), published in 1558, in which the poet imagines plundering the ruins of Rome to furnish the French king’s new palace at Fontainebleau:

“Unable to give you these ancient works . . . / I give them to you, Sire, in this little picture, painted, as best I could, with poetic colors / Which, . . . if you deign to view it in its best light, / will be able to boast of having pulled from the tomb the dusty remains of the ancient Romans. / May the gods one day give you the good fortune / to rebuild in France such greatness / that I would willingly paint it in your language.”

Du Bellay’s intent was not merely to dust off the ruins of a distant Roman past to refurbish the king’s present palace, but rather to actively revivify ancient relics in the modern French vernacular. In Défense et illustration de la langue française, Du Bellay expresses his vision for the future of the French vernacular through an extended horticultural metaphor, in which he defends the natural potential of the French language to bear fruit while criticizing his contemporaries for their negligence:

“I can say as much of our language, which is just beginning to flower without bearing fruit, or rather, like a seedling and fresh shoot, has not yet flowered, much less yielded all the fruit it is capable of producing. That comes certainly not from any defect in its nature, as apt to engender as others, but through the fault of those who have had it in their care and have not sufficiently tended it; but like a wild plant in that same uncultivated place where it was born, they have let it grow old and nearly die, without ever watering it, pruning it, or protecting it from the bramble and thorns that shaded it.”

Du Bellay’s defense of the French vernacular has a distinctly militant quality to it. In Les antiquitez de Rome, Du Bellay describes his appropriation of Greek and Italian poetic forms with graphic metaphors of cannibalism: “By imitating the best Greek authors, transforming themselves into them, and after having thoroughly digested them, converting them into blood and nourishment, selecting, each according to his own nature and the topic he wished to choose, the best author, all of whose rarest and most exquisite strengths they diligently observed.”

By comparison, the horticultural metaphors scattered throughout Défense et illustration de la langue française seem relatively tame. But even here, Du Bellay’s vision for the future of the French vernacular beats an unmistakably militant drum; by describing the present state of the French vernacular as a dormant and fallow land laid to ruin by the negligence of its inhabitants, Du Bellay anticipates the imperialist logic of nineteenth-century French colonialists, who justified the colonial conquest of North Africa by describing its stark landscape as a savage wilderness that had yet be domesticated (for more on this, see Edward Saïd’s canonical introduction to Orientalism).

In an earlier scene in Les glaneurs et la glaneuse, when a viticulturist in the vineyards of Pommard, an appellation d’origine controlée (A.O.C.), or “protected designation of origin,” in the famed Burgundy region of France, recites from memory a few lines from Défense et illustration de la langue française, which Du Bellay is he evoking: the patient horticulturalist or the violent imperialist? Varda’s camera scans the vineyard ground, contemplating bunches of second-crop grapes, known as verjus, that have been cut from vine and left on the ground to rot. Varda interviews another Burgundy winegrower, who justifies the destructive and predatory practice as an unfortunate but necessary measure to protect to integrity and value of the Burgundy name.

8.

By the time I moved to Paris in January 2017, the massive refugee encampment known as La Jungle near Calais in northern France had been forcibly evacuated, and thousands of displaced refugees had migrated south to Paris to find shelter beneath the elevated tracks of the metro line that runs between La Chapelle and Barbès Rochechouart. The urban landscapes of Varda’s Les glaneurs et la glaneuse had been transformed by a new crop of migrant gleaners, in search of something more substantive than bunches of wilted parsley and pale endives leftover from the morning market. Having fled conflict and economic destitution in former French colonies and protectorates in Africa and the Middle East, thousands of migrants had convened upon the French capital to claim their rightful part of the French ideal of universal equality, a revolutionary concept to which Du Bellay had given expression as early as the sixteenth century.

I chose to put down roots in the nineteenth arrondissement because of its relative affordability, but also because its diverse, working-class character appealed to my bohemian sensibilities. The day I moved into my new apartment on the Rue de Meaux, I went walking in the neighborhood and came across a densely graffitied wall across from an elementary school on the Rue Henri Noguères, where even the trees and the lampposts are covered in a constantly mutating display of street art.

Similar displays of street art have transformed the nineteenth arrondissement into a vast urban gallery. The bridge over the train tracks of the Gare de l’Est on the Rue Riquet is covered with giant portraits of African American icons, from Rosa Parks to Jimi Hendrix and Malcolm X, and on the bridge over the Bassin de la Villette on the nearby Rue de Crimée, someone has scrawled the unforgettable lyrics to John Lennon’s “Imagine.” On my way to the Laumière metro stop around the corner from my apartment, I was delighted to find that Jérôme Mesnager, a world-renowned graffiti artist, had tagged the glass window of the corner café with his characteristic white silhouettes of the human form, a celebratory symbol of life and liberty. On the retaining wall of a Catholic high school on the Rue Bouret, around the corner from the Marché Secrétan, Mesnager has illustrated the Buddhist Eightfold Path to Enlightenment as a hopscotch game to Nirvana.

The more I looked, the more I found traces of the neighborhood’s progressive past. Henri Noguères, the namesake of the graffitied street mentioned above, was an important French socialist who participated in the French Resistance against the German Occupation during the Second World War. And on the southwestern edge of the neighborhood, the busy intersection between the Canal Saint-Martin and the Bassin de la Villette bears the name of Jean Jaurès, the founder of modern French socialism.

In contrast to the picturesque cafés and cobblestoned streets of Montmartre to the west and the artists’ studios and cagey music clubs of Belleville and Ménilmonant to the southeast, the nineteenth arrondissement has an understated appeal. This is the Paris I had been looking for all these years, with laundromats and a home improvement depot and a couple of Franco-Maghrebi brasseries that offer couscous specials on Fridays. There are no boutique culinary shops here, selling artisanal chocolate or regional jam or organic olive oil, but there is an excellent halal butcher, a fishmonger, a greengrocer, a wine seller, a fromagerie, and an African wholesale grocery that sells plantains and fresh sugar cane and bulgar wheat in bulk.

And the neighborhood has its charm, too. On sunny days, the decommissioned barges anchored along the Bassin de la Villette are transformed into floating bars, and the outdoor terraces of the Panane Brewing Company and the Pavillon des Canaux are bursting with locals unburdened by crowds of curious tourists. Up the hill from the canal, the Parc des Buttes Chaumont, with its forested paths and hidden grottos, stands in stark contrast to the manicured paths of the Jardin du Luxembourg in the sixth arrondissement or the Jardin des Tuileries, which stretches between the Louvre and the Place de la Concorde, where stark rows of stunted trees have been aggressively pruned into geometric shapes. At the center of the Buttes Chaumont, on a rocky crag accessible only by bridge, the Temple de la Sibylle, an imitation of the ancient Roman Tempio di Vista in Trivoli, offers an unexpected view of Sacre Coeur, a silhouette against the sunset.

The nineteenth arrondissement is uncharted terrain; I am an explorer here. But as an outsider, and a critically minded one at that, I am painfully aware that my presence here potentially contributes to the neocolonial forces of urban gentrification. The cycle is insidious.

I value this neighborhood because it is the place where I have finally found a home in Paris after nearly a decade of traveling in France. But in ascribing value to this neighborhood, and by proudly displaying it to the friends who have visited me in Paris, I transform it; I leave my mark. Like the generous individuals who deposit found objects at the Bureau des Objets Trouvés, I become its inventeur; its value consists in the quality of having been found.